Why We Make the Doughnuts

Good works are a finite resource that must be distributed according to the guidance of a charitable prudence.

In this classic commercial, Fred the Baker is torn between a devil, who urges him to get a decent night’s sleep, and his guardian angel, who advises him get up at a presumably ungodly hour to make fresh doughnuts for “all the nice folks.”

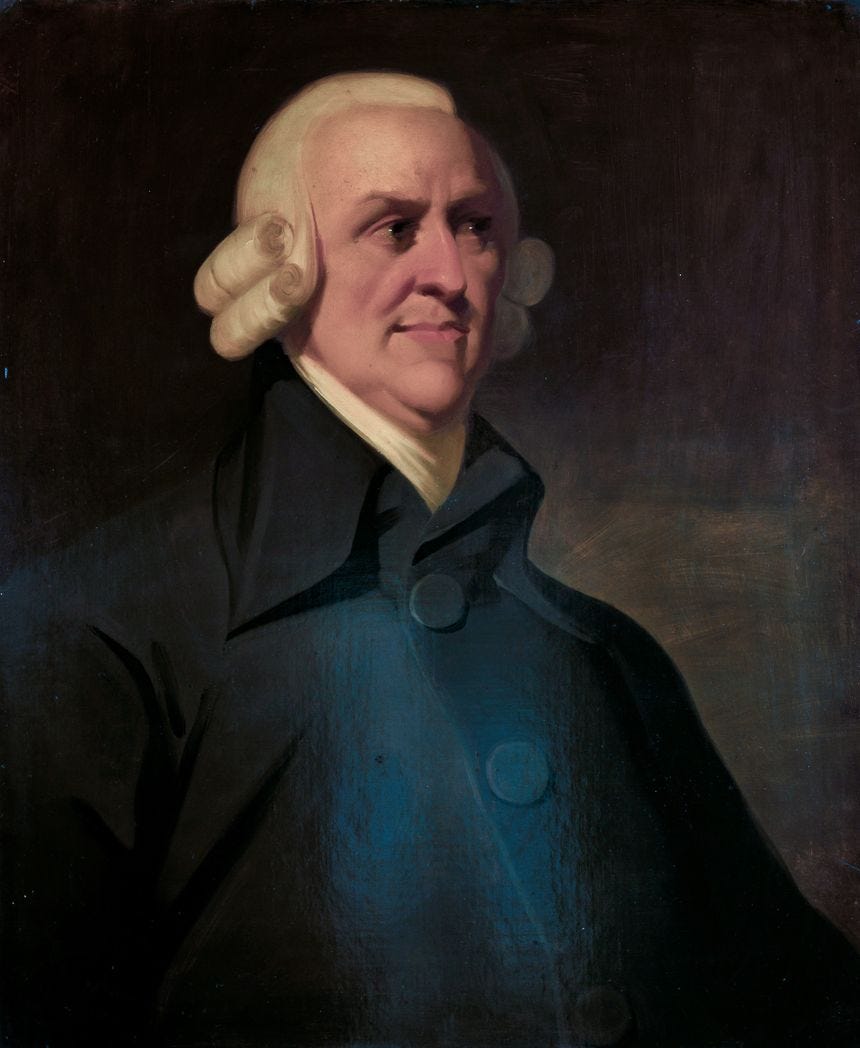

The conceit, that Fred is robbing himself of beauty rest for love of us, was one Adam Smith long ago taught us to scoff at.

Near the beginning of his Wealth of Nations, Smith disabuses us of the notion that we may expect to receive the much-needed help of our brethren “from their benevolence only.” “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

Smith’s point is not simply that, if we want the “good offices” of others, we must appeal to their “self-love” rather than their “charity.” He also argues that it is self-regard that “encourages every man to apply himself to a particular occupation, and to cultivate and bring to perfection whatever talent or genius he may possess”—to the (unintended) advantage of his fellows.

In other words, the qualities we admire most in ourselves and others are an outgrowth of selfishness rather than generosity!

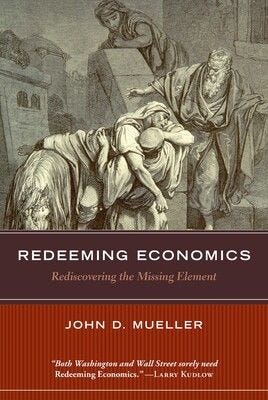

As John Mueller points out in Redeeming Economics, Smith’s praise of selfishness is true in a sense, but presented in highly misleading terms. While it is fair to say that self-love is essential to the habits of personal development and mutual exchange that make the world turn, it is mistaken to present self-regard as standing in a binary relationship with benevolence.

Instead, Mueller explains with the aid of St. Thomas Aquinas, the command to love one’s neighbor as oneself implies that salutary self-love is the foundation of altruism. When we care for ourselves and cultivate our own gifts, we become more benevolent—willing the good of others—and better able to practice beneficence: doing good for others. The order of charity therefore demands that we begin by helping ourselves, and also that in helping others, we prioritize helping them to help themselves.

Benevolence and beneficence are intimately related but practically distinct. While goodwill can and ought to be universal, good works are a finite resource that must be distributed according to the guidance of a charitable prudence. Though beneficence will inspire us to give to others without counting the cost, benevolence will demand that we also accept payment for our services insofar as it is necessary to enable us to provide for ourselves and those who depend on us.

The fair exchange of goods, though motivated by healthy self-love, is at the same time an expression of benevolence. An unhealthy selfishness, seeking to profit at the expense of others, is something altogether different. Mueller calls it crime.

Getting back to the baker: if he were indeed selfish to point of malevolence, he would get up at the crack of dawn to rob a bank, or lace our pastries with addictive chemicals. To the extent that a given confectioner does trade our health for his own profits, we may conclude that he is less benevolent than he might be. (And also that we are less savvy shoppers than we ought to be.)

To the extent that the baker is laboring to provide genuine "good offices" at a fair price, thereby supporting himself and his family, while providing his customers with the opportunity to enjoy the fruits of his talents and enterprise, his self-love is in fact a vital manifestation of well-ordered charity.

If you enjoyed these reflections, please forward to a friend!

Great work!!!