A Constitution Day Reflection and Invitation

The very first representatives of the United States of America belonged to the Continental Congress (1774-1781), under whose leadership thirteen colonies of Great Britain became “free and independent states.”

In one of its greatest acts, that Congress issued the Declaration of Independence, acknowledging and justifying the tremendous perils into which its members were placing themselves and the peoples they represented in attempting to dissolve the bands connecting them to a global empire.

The risk was not merely that the signers might be hanged for treason, or that the declaration would provoke a war, with certain bloodshed and no guarantee of success—though all that was true.

An additional risk was that, after defending their right to abolish one government, and “institute a new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness,” the American people would end up with a government no better than before.

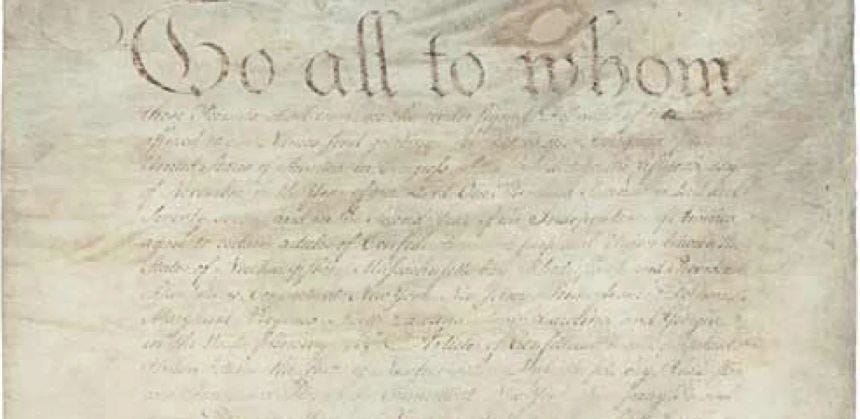

This is precisely what happened. Under our first constitution, the Articles of Confederation (1781-1789), United States government was a shambles. Having escaped the clutches of an overbearing overseas dominion, the peoples of the states had elected to establish an exceedingly weak federal government, which proved unable to hold them together on essential matters of foreign and domestic policy.

It soon became clear that the incapacity of a government is as much a threat to the rights of citizens as is its overgrowth. Fearing a loss of liberty by anarchy or foreign conquest, a chagrined people sent new representatives to Philadelphia in 1787 to find the remedy.

Alexis de Tocqueville describes the result as follows:

If ever America was capable of rising for a few moments to the high level of glory that the proud imagination of its inhabitants would like constantly to show us, it was at this supreme moment when the national power had, in a way, just abdicated authority. . . .

What is new in the history of societies is to see a great people, warned by its legislators that the gears of government are grinding to a halt, turn its attention to itself, without rushing and without fear; sound the depth of the trouble; keep self-control for two whole years, in order to take time to find the remedy; and, when this remedy is indicated, voluntarily submit to it without costing humanity either a tear or a drop of blood.

When the insufficiency of the first federal constitution made itself felt, the excitement of the political passions that had given birth to the revolution was partially calmed, and all the great men that it had created still lived. This was double good fortune for America. The small assembly, which charged itself with drafting the second constitution, included the best minds and most noble characters that had ever appeared in the New World. George Washington presided over it.

This national commission, after long and mature deliberations, finally offered to the people for adoption the body of organic laws that still governs the Union today.

Among the most important of the innovations made by the Constitutional Convention was the adoption of a government firmly planted on the twin foundations of separation of powers, and checks and balances.

Under the Articles of Confederation, the Union had legislative powers, but no executive or judicial powers. Hence laws could be made, but not enforced.

In the states, all three powers existed, but in most they were unbalanced, giving one branch the ability to manipulate the others, and therefore leaving room for corruption to take hold.

Though no one came to the Philadelphia convention with anything like our current constitution in mind, their fruitful debates resulted in a design assuring that the federal government would be able to make, enforce, and adjudicate laws.

To accomplish this, each function had to be entrusted to a separate branch, but each branch had to be given sufficient ability to interfere with the others, in order to protect itself against their incursions.

To this day, this combination of the independence and interplay of our branches profoundly shapes the way public policy is made and implemented, and the way political controversies arise and are settled.

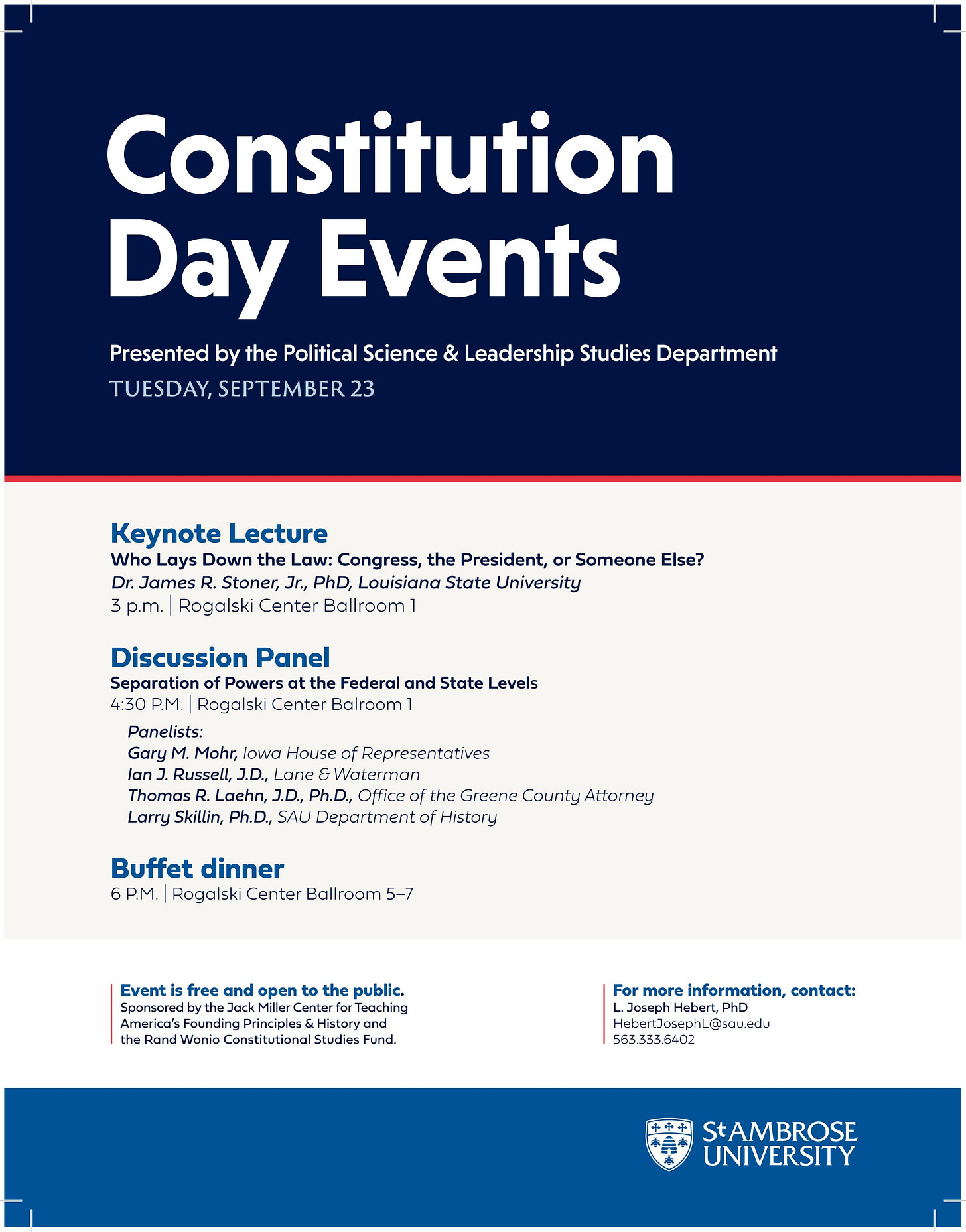

Please join us on Tuesday, September 23rd, for a Constitution Day discussion of separation of powers at the federal and state level.

Our keynote speaker will be James Stoner of Louisiana State University, a leading expert on the common law roots of American constitutionalism. He will be speaking on “Who Lays Down the Law—Congress, the President, or Someone Else?”

His talk will be followed by a panel including Iowa Representative Gary Mohr, Ian Russel of the law firm Lane & Waterman, Greene County Attorney Thomas Laehn, and St. Ambrose University history professor Larry Skillin.

Hope to see you there!

Questions? Comments? Suggestions for future posts? Please comment and share!